Why we teach our students progressive enhancement

With new CSS features seemingly coming out every week, I’ve been doing more and more progressive enhancement (PE) in my projects. It’s also a big part of what we teach our students at the Associate Degree We’re always looking for guest lecturers, contact us!Frontend Design and Development at the University of Applied Sciences in Amsterdam.

A famous example of PE is the escalator, when an escalator breaks down it can still be used as stairs, which satisfies the core task of an escalator: allowing people to get to a different floor.

So progressive enhancement is not about preventing failure, it’s about defining what must always work.

We teach our students to build features in three steps:

- First determine the core user task, and implement it in the most robust way possible in HTML

- Layer on additional capabilities with CSS

- And finally (optionally) add JavaScript when the browser allows (or needs) it

Graceful degradation is another strategy often mentioned in the same breath or confused with progressive enhancement. It assumes you start with a fully featured experience and then tries to prevent it from breaking in less capable environments. This is actually a solid strategy for things like animation or visual effects, where failure doesn’t block the core task. For core functionalities I think this approach is risky, if something breaks the feature may break with it. PE avoids this by defining what must work first and only layering on features when they’re available.

Core tasks

Identifying the core task means determining what must succeed for a feature to be useful at all.

Most developers often bundle multiple ideas together. Filtering, for example, is usually treated as a client-side interaction problem. But at its core, filtering is really about narrowing down information. And HTML already gives us a way to do that natively: a form that submits a request and returns a refined result.

The same thing applies to disclosure patterns like FAQs, read more buttons or modals. The core task is not the animation or the toggle, it’s that the information is available in the first place. If all interactivity disappeared, could a user still read what they came for?

When you deliberately design the worst acceptable experience first, everything that comes after becomes an enhancement instead of a requirement.

HTML first

Once you have a clear core task for your feature, the next step is to look at what HTML already provides. While HTML is often used to ‘just’ structure content, a surprising amount of built-in behaviour has been added over the years.

The <details> element, for example, offers a native way to disclose content. It works well for accordion items often used for FAQs, read-more sections and even tabs. The details element has been supported across browsers since 2020 (source: MDN), and when supported it adds keyboard support and some built-in accessibility.

But even if a browser doesn’t support the element, the content doesn’t disappear, it’s simply shown by default. HTML is quite forgiving in that way: if a browser doesn’t know an element it will still just render it as if it’s a <div>.

That’s a pattern you see in many native HTML features. Forms still submit without JavaScript. Buttons still work. Links still navigate. Even in very old browsers, these basics keep working.

What if there’s no JS?

Progressive enhancement is often framed as making sure websites work without CSS or JavaScript. It was actually mentioned so many times during the Minor Web Design & Development that one of the students added ‘what if JavaScript is turned off?’ in the stickerpack she created.

That framing puts a lot of emphasis on the failure scenarios and not enough on what the intent is of building with progressive enhancement in mind. The real goal of PE, in my opinion, is to offer a consistent experience regardless of browser, browser version, or user preferences, but the experience doesn’t have to be exactly the same everywhere.

We already accept this idea in responsive design. No client expects the desktop and mobile versions of a site to be identical; they expect them to be appropriate for the context they’re used in. Differences between browsers should be treated the same way.

Building for the modern web

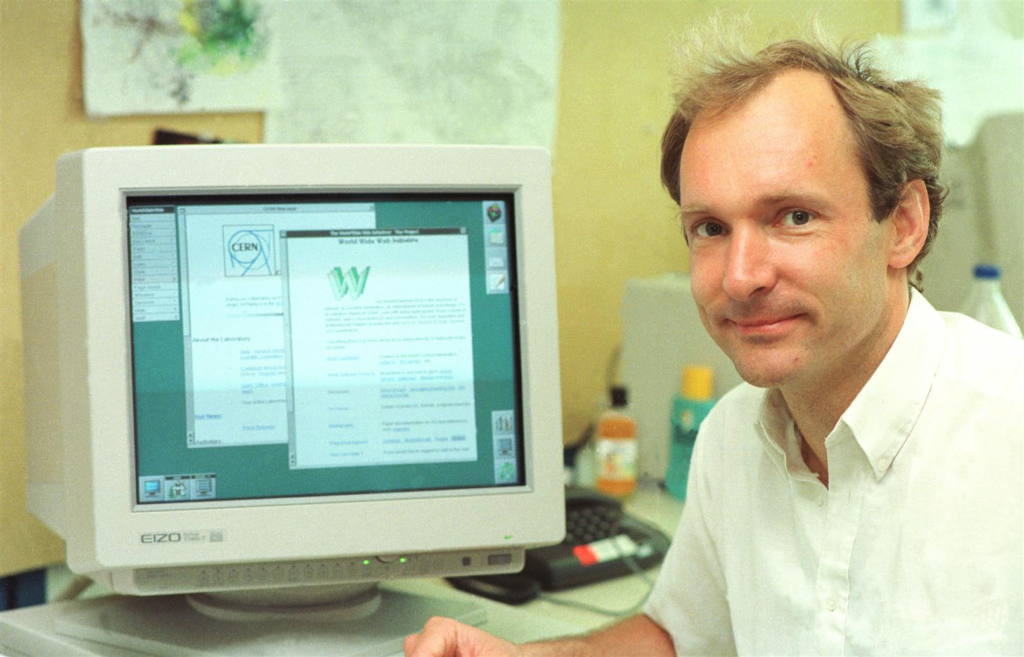

The web hasn’t been a single fixed target since it was solely running on Sir Tim Berners Lee’s computer at CERN. It runs on different devices, across different browsers, with different input methods, and under different user preferences.

By building with progressive enhancement in mind we take that reality seriously and make sure that the most important parts of our features always work. Everything added after that; like layout, animation and interaction builds on top of a solid foundation.

It doesn’t mean your experience needs to be boring or limited, though, it actually allows you to experiment, add small delights and to use new browser features without worrying it will break things for users that can’t- or prefer not to use them yet.

Users with updated browsers might be rewarded with smoother transitions or nicer interactions, while users with older browsers aren’t punished by not being able to get the task done.

Progressive enhancement is about building something robust, that works everywhere, and then making it better where possible.

Last updated: January 15, 2026

Replies 1

Hahah curious to hear your take on it! Glad this resonated with you 🙂

Bookmarks 1

Why we teach our students progressive enhancement | Blog Cyd Stumpel

Progressive enhancement is about building something robust, that works everywhere, and then making it better where possible.

Mentioned on other websites: 1

Likes 33

Reposts 13

Webmentions are a way to connect with other people who have shared your work.